Author: Jethro Johnson

Contributors:

Updated: 11 May 2020

DADA2: Improving Taxonomic Resolution

Introduction

Clustering 16S sequences into OTUs has historically served two purposes:

-

It has removed minor artifactual sequence variants due to PCR amplification and sequencing errors.

-

It has collapsed legitimate sequence variation that exists between closely related bacterial taxa.

While the latter may not always be desirable, it stands to reason that you can’t distinguish between bacterial taxa whose 16S sequences vary at a rate that is lower than the error encountered on a particular sequencing platform.

Recently, a number of tools have been developed with the goal of removing PCR and sequencing errors in 16S data (‘denoising’). Examples include Minimum entropy decomposition, UNOISE, DADA2, and Deblur. For a recent comparison of some of these tools, see here.

These approaches collectively claim it is now possible to distinguish between sequences that differ by as little as one nucleotide. In consequence, they argue that denoised sequences (variously called exact sequence variants (ESVs), amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), or zero-radius OTUs (ZOTUs)) should replace conventional OTUs as the unit of measurement in 16S studies.

While the main practical session is focused on conventional OTU analysis. This session contains an introduction to sequence analysis based on the DADA2 pipeline.

1. Fetching Data for DADA2 Analysis

2. Open DADA2 and Plot Read Quality

3. Trim and filter forward and reverse reads based on quality

4. Denoise reads with DADA2

5. Genererate amplicons and create an abundance matrix

6. Assign Taxonomy to DADA2 Amplicon Sequence Variants

1. Fetching Data for DADA2 Analysis

For this session we’ll use a slightly different set of input samples. Start by creating a run directory and copying the data to this location.

# Create a working directory for this session

cd ~/MCA/16s/

mkdir Session1.3

mkdir Session1.3/fastqs

cd Session1.3/fastqs

# Copy the fastq files for three samples to this location

cp ~/additional_data/sample* .

# Note these files are gzip compressed, but it is still possible to view them

# using the linux pipe.

zcat sample1_trimmed.fastq.1.gz | head -4

2. Open DADA2 and Plot Read Quality

As the DADA2 package is written entirely in R, most of this session will be carried out in RStudio.

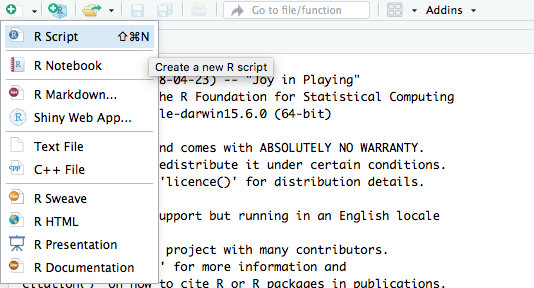

Nagivate to your RStudio session and open a new R script.

Remember, you can write (and comment!) code in your new R script then run it via

the R terminal, either by copying and pasting it across, or by highlighting

it and selecting the Run icon in the top-right side of your script window.

Having opened RStudio, set your working directory to be the location of the run directory created in step 1.

# Find out which working directory R is running in?

getwd()

# Set your working directory and check the contents

setwd('~/MCA/16s/Session1.3')

list.files('.')

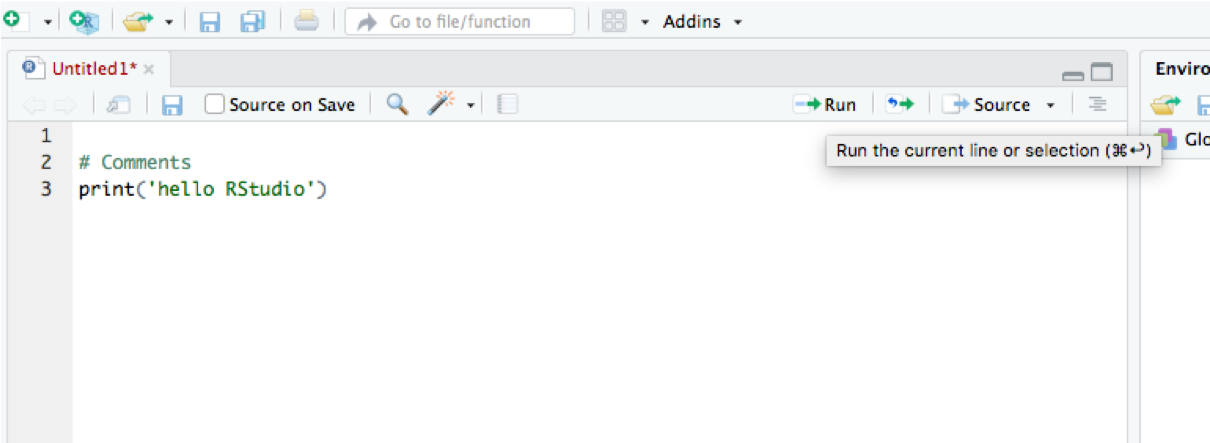

list.files('./fastqs')Note that the fastq files have been trimmed to remove PCR and sequencing primers.

However, they have not been trimmed to remove low quality sequences at the 3’

end of reads. We will use the DADA2 function plotQualityProfile() to visualize

the distribution in quality at each base in the forward and reverse reads from

the first sample.

# Create avectors in R containing details of forward and reverse reads

fastq1 <- sort(list.files('fastqs', pattern='.fastq.1.gz', full.names=T))

fastq2 <- sort(list.files('fastqs', pattern='.fastq.2.gz', full.names=T))

# Plot the read quality distribution for each sample pair

plotQualityProfile(c(fastq1, fastq2))

In this plot lines show the mean (green), median (orange) and 25th/75th percentiles (dashed) of the quality score at each base position in the forward and reverse reads.

A side note on handling data with R

When working on the bash command line, we have tended to use for loops to run the same command for multiple samples. R is not optimised for running for loops and it takes a fundamentally different approach. For further discussion of why this is have a look at the family of apply functions in R, as well as the fundamentals of the split-apply-combine stragegy.

For the purposes of this practical session note that, rather than using a for loop

to run plotQualityProfile() above, we passed all the files to the function as a

single character vector. This is typical of how R deals with repetitive tasks.

3. Trim and filter forward and reverse reads based on quality

The first step in processing reads with DADA2 is to remove poor quality sequence. In our main 16S analysis session this step wasn’t performed. Instead we were relying on the FLASh assembler and downstream OTU calling to account for low quality sequence.

Similar to our bash code, it’s necessary to define the names of input and output files before running the filtering step.

# Create a subdirectory from within R to contain quality trimmed sequences

dir.create('fastqs_trimmed')

# This subdirectory now appears in your working directory

list.files('.')

list.files('./fastqs_trimmed')

# Fetch a list of sample names from the list of forward reads

sample.names <- sapply(strsplit(basename(fastq1), '_'), `[`, 1)

# Create vectors of output filenames for both forward and reverse reads

fastq1.filtered <- file.path('fastqs_trimmed', paste0(sample.names, '.fastq.1.gz'))

fastq2.filtered <- file.path('fastqs_trimmed', paste0(sample.names, '.fastq.2.gz'))

# Run quality trimming and filtering in DADA2

out <- filterAndTrim(fwd=fastq1, filt=fastq1.filtered,

rev=fastq2, filt.rev=fastq2.filtered,

truncLen=c(260, 260),

maxEE=c(2,2),

multithread=T)

list.files('./fastqs_trimmed')

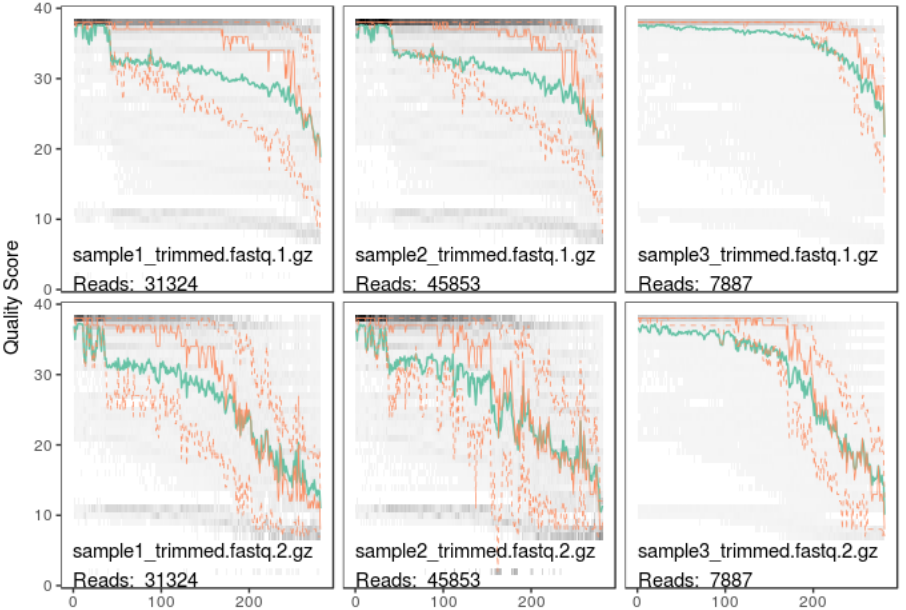

print(out)In the code above, we’ve set the minimum permissible truncated length of for a sequence to be 260bp for both forward and reverse reads. These were originally 2x300bp reads generated on the Illumina MiSeq platform to span the (~500bp) V1-V3 region. However, 20bp has been trimmed from the 5’ end of each read during adapter removal. This minimum lengths used above have therefore been selected to ensure (minimal!) overlap between reads during amplicon assembly.

The histogram below shows a typical distribution in the length of amplicons generated from a human gut microbiome study.

What biases may be introduced by setting a stringent

truncLenvalue?

For more information on the arguments supplied in the quality trimming and filtering step type

?filterAndTriminto the R terminal.

Try altering

truncLenand replacingmaxEEwith a minimum quality score (minQ) to see what effect these parameters have on the number of reads remaining after filtering.

4. Denoise reads with DADA2

Denoising in DADA2 is a two step process, first it models the expected error the forward and reverse reads, then it removes this error to create a ‘corrected’ read set. For further detail see the methods and supplementary material in the original DADA2 publication.

# Model error in forward and reverse reads

error1 <- learnErrors(fastq1.filtered)

error2 <- learnErrors(fastq2.filtered)

# Remove exact replicate sequences

dereplicated1 <- derepFastq(fastq1.filtered, verbose=T)

names(dereplicated1) <- sample.names

dereplicated2 <- derepFastq(fastq2.filtered, verbose=T)

names(dereplicated2) <- sample.names

# Then apply the DADA2 denoising algorithm

corrected1 <- dada(dereplicated1, err=error1)

corrected2 <- dada(dereplicated2, err=error2)

corrected1

corrected2

5. Genererate amplicons and create an abundance matrix

Having corrected sequencing errors in forward and reverse reads, the remaining steps are to merge read pairs into amplicons, remove chimeras, and to calculate the abundance of each amplicon in each sample.

# Combine the forward and reverse read into a single set of amplicons

amplicons <- mergePairs(dadaF=corrected1, derepF=dereplicated1,

dadaR=corrected2, derepR=dereplicated2,

verbose=T)

# Generate a count matrix containing the counts for each denoised sequence

sequence.tab <- makeSequenceTable(amplicons, orderBy='abundance')

# The rows of this matrix are the samples

rownames(sequence.tab)

# The columns are the sequences

colnames(sequence.tab)

# Remove chimeras directly from the count.matrix

sequence.tab.nochimeras <- removeBimeraDenovo(sequence.tab, verbose=T)

# Finally, it's possible to write the denoised amplicons to a fasta file

uniquesToFasta(getUniques(sequence.tab.nochimeras), 'dada2_esvs.fasta')How many unique amplicons were created using the DADA2 denoising pipeline?

6. Assign Taxonomy to DADA2 Amplicon Sequence Variants

Within the DADA2 pipeline, it is also possible to assign taxonomy to denoised

sequences via a two step process. The first step assignTaxonomy() is a wrapper

for the method introduced in our previous 16 analysis session. As this method only returns classifications

to genus level. The second step addSpecies() attempts to find exact matches

for each sequence in a curated reference database.

First, it’s necessary to retrieve the reference databases for taxonomic and species assignment. A selection of formatted reference databases can be found here. In this example we will begin by downloading reference databases derived from the NCBI 16S database and the RDP database.

# In your bash terminal cd into the current working directory

cd ~/MCA/16s/Session1.3

# Download the database used to train the RDP classifier

curl -O -J -L https://zenodo.org/record/2541239/files/RefSeq-RDP16S_v2_May2018.fa.gz?download=1

# Download the database used for exact sequence matching

curl -O -J -L https://zenodo.org/record/2658728/files/RefSeq-RDP_dada2_assignment_species.fa.gz?download=1

ls -lHaving downloaded the reference databases, return to R to perform taxonomic assignment.

# Assign taxonomy to genus level

taxonomy.table <- assignTaxonomy(seqs=sequence.tab.nochimeras,

refFasta="RefSeq-RDP16S_v2_May2018.fa.gz",

multithread=T)

# Assign species via exact matching

taxonomy.table <- addSpecies(taxtab=taxonomy.table,

refFasta="RefSeq-RDP_dada2_assignment_species.fa.gz",

verbose=T)

# As row names in the resulting table are the sequences

# remove them before viewing.

taxa.print <- taxa

row.names(taxa.print) <- NULL

taxa.print <- as.data.frame(taxa.print)

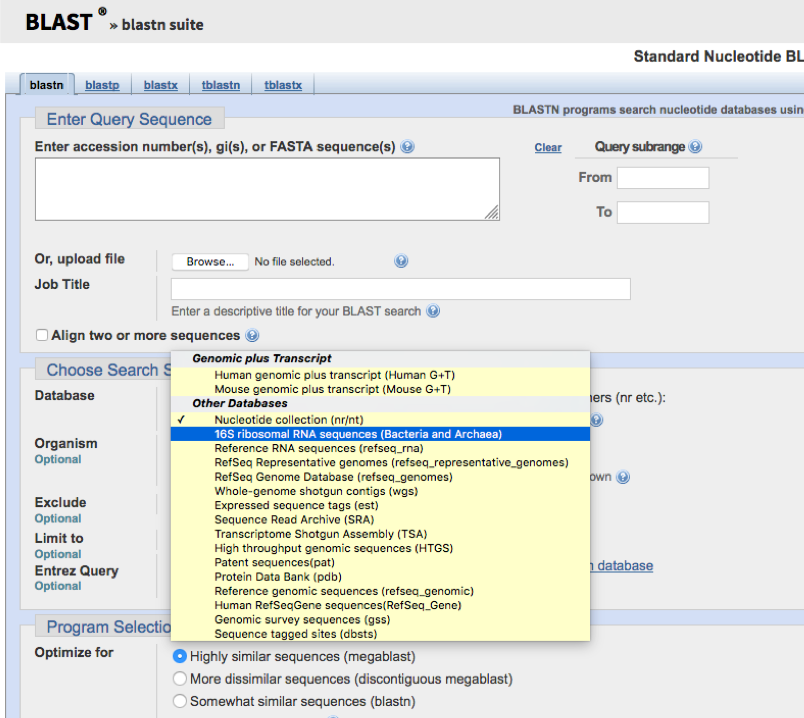

View(taxa.print)Alternatively, it is possible to assign taxonomy to the denoised amplicon sequences by using the NCBI nucleotide BLAST tool. This can be done by copying and pasting individual sequences into the online BLAST portal. Then selecting the highly-curated NCBI 16S rRNA database as a reference.

Try running BLAST for the most and least abundant ASVs in your output fasta file.

Try running BLAST against the NCBI Nucleotide collection database, rather than the 16S rRNA database.

Note that it’s also possible to install BLAST locally and run it from the commandline. However, if you do this, for taxonomic assignment, be very careful about the arguments you provide.

Conclusions

DADA2 and other denoising algorithms provide a different approach to dealing with sequencing error compared to more traditional OTU-based analysis.

In OTU analysis sequencing error is removed by collapsing sequences at an identity threshold that is (hopefully!) higher than the error rate encountered on a particular sequencing platform. DADA2 models this error before removing it from each (unique) sequence.

Both approaches have strengths and weaknesses. Proponents of denoising algorithms argue that they have two major theoretical advantages:

-

First, they remove the need to collapse legitimate sequence variation that may occur between closely related taxa. This enables finer taxonomic resolution in 16S studies.

-

Second, the ability to identify exact sequences means sequences can be compared across studies. By contrast, the manner in which OTUs are generated means they are unique to the study in which they are derived.

While these are significant advantages, biological judgement is required when interpreting denoised amplicon data. For example, how many of the denoised amplicon sequences could confidently be classified to species level? To what extent does this depend on the completness and accuracy of the 16S rRNA reference databases?

Another interesting point to consider is that the three samples analyzed in this session were drawn from a mock community made up of 36 bacterial species. The list of included species is given below:

| Actinomyces naeslundii MG-1 | Akkermansia muciniphila | Bacteroides caccae |

| Bacteroides vulgatus | Bifidobacterium dentium | Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis |

| Corynebacterium accolens | Corynebacterium amycolatum | Corynebacterium matruchotti |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Escherichia coli | Eubacterium brachy |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum | Gardnerella vaginalis |

| Lactobacillus crispatus | Lactobacillus gasseri | Lactobacillus iners |

| Lactobacillus jensenii | Lautropia mirabilis | Moraxella catarrhalis |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | Prevotella melaninogenica | Prevotella nigrescens |

| Prevotella oralis | Propionibacterium acnes | Rothia dentocariosa |

| Ruminococcus lactaris | Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus | Streptococcus agalactiae |

| Streptococcus mutans | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Streptococcus sanguinis |

| Tannerella forsythia | Treponema denticola | Veillonella parvula |

How many ASVs were generated by DADA2 compared to the number of species in this community?

How many of the species above were identified by the different taxonomic classification approaches?

What happens when you run these three samples through the OTU pipeline introduced in the main session?

What happens when you increase the identity threshold used for OTU clustering from 97% to 99%?

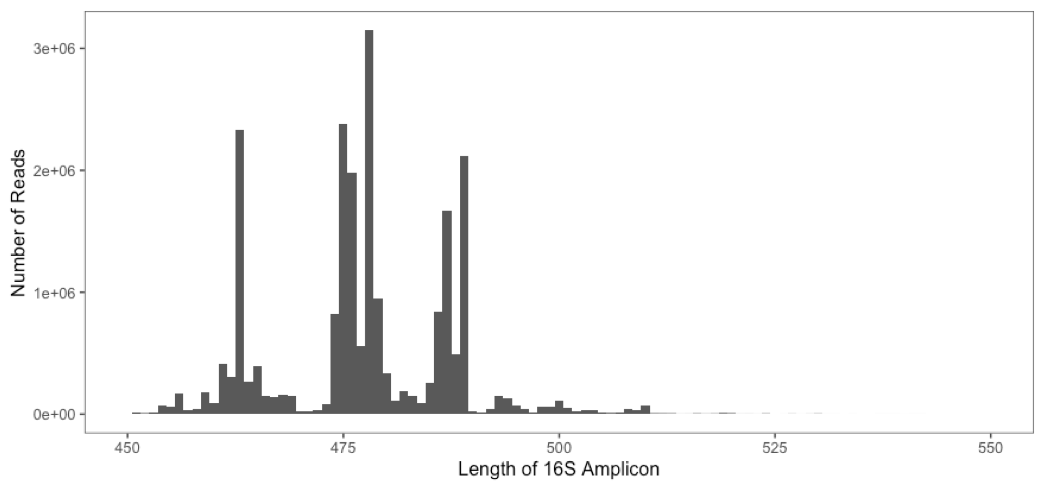

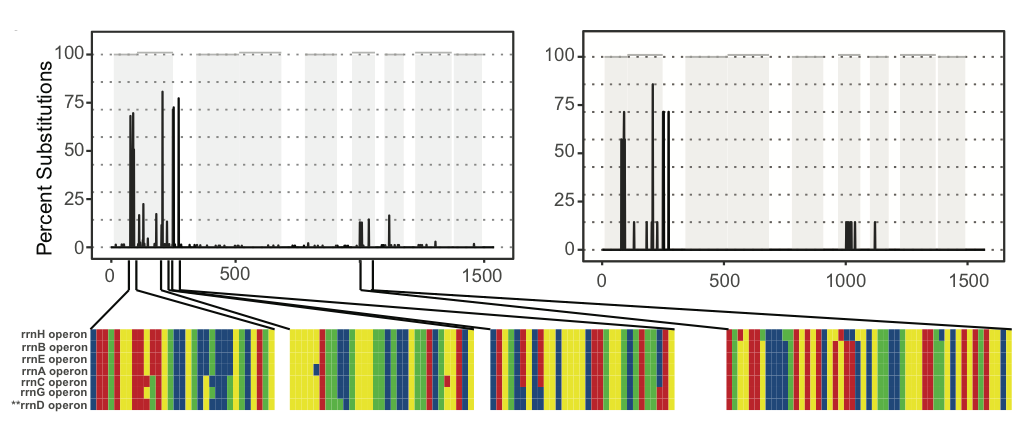

One final point to consider when interpreting ASVs is that many bacteria contain multiple copies of the 16S gene that may vary in their sequence composition. The image below shows the observed (left) and predicted (right) frequency of nucleotide substitutions occurring across the seven (~1500bp) 16S genes present in the genome of Escherichia coli strain K-12 subst. MG1655. In total five of these seven 16S genes are unique, while the remaining two are identical.

How many E. coli ASVs were detected by DADA2?